SYMBIOSIS IN A CONTAINER IN A FRIDGE IN A MESSY APARTMENT — FERMENT PROJECT

Reflecting on care and maintenance through the process of creating, maintaining and worrying about a nukadoko fermentation bed.

MAY 2023 / NOV 2023

This doesn’t feel right, what did I do wrong.

I mutter to the dry, powdery mix of rice bran,

salt and water I’m struggling to knead together. Second guessing myself, I check the recipe again:

1kg rice bran, toasted

(didn’t toast it, it’s probably fine)

130g fine sea salt

(used Kosher salt, that’s probably fine, too,

I don’t know)

1000ml purified water, not tap — chemicals

in it could harm your microbes

(fuck, I used tap water)

I. TOUCH FERMENTATION

Maybe I should start over. I continue to press the wrongly prepped rice bran, salt, and water together. Each fistful clumps together more than the previous, gradually forming a dense paste. I’m just going to see what happens with this un-toasted, non-sea salt, tap water nukadoko. Still questioning every decision I’ve made up to now, I add broken up sheets of kombu and dried chili peppers into the bowl and mix them into the paste.

Half of the rice bran-salt-kombu-chili-water paste then gets packed into the bottom of a rectangular enamel container — I googled “nukadoko container” and ordered two different sizes just in case — then I nestle cabbage wedges into the paste and pack the remaining mixture on top of them before sealing the container and setting them aside in an empty corner of my countertop. Now all I can do is wait and worry.

Translated as Nuka [者物(rice bran)] + Doko [葋(bed)],1 nukadoko is a fermented rice bran bed for pickling vegetables. Its main ingredient is rice bran (nuka), the hard outer layer of the rice cereal grain that gets ground and polished off to produce white rice. To make the nukadoko, you mix rice bran with salt, water, dried kombu, dried chiles and vegetables before leaving it loosely covered at room temperature for ten days. Over those ten days, the nukadoko has to be turned twice a day to help the Lactobacillus in it survive, mature, and ferment the vegetable chunks. During the beginning of its life, the nukadoko paste itself feels like damp sand and smells toasty and malty. It initially just tastes salty and a little nutty — the tongue and taste buds can easily discern each individual ingredient. After the first ten days, the nukadoko and its resident microbes are better established in their home and only need to be mixed once a day. By that point, the rice bran paste is soft, having absorbed more water from the vegetables buried in it.

I don’t remember first learning about it, but I’ve thought about starting a nukadoko pickling bed for at least six or seven years now. Maybe I was drawn to the idea of being someone who ferments things and who always has fresh, homemade pickles on hand. Maybe I wanted to feel more authentically “Asian” and start something that I could, in theory, share with the next generation. But I’m mixed Filipino and white and grew up in the US — making a Japanese fermentation bed to feel more connected to my heritage rings hollow. Whatever the reason, I’ve wanted to make a nukadoko bed for a long time.

Before finally starting it, I thought that I’d find joy and satisfaction from the process of mixing the bed daily. That we’d fall into a rhythm and a schedule: maybe every third day I’d gently, lovingly take out the enamel container from my fridge and sink my fingers into the bed, turning it like loose soil and pulling out perfectly pickled vegetables. I also thought I’d magically become someone who eats a lot of pickles (I’m not, but I feel like I should be). I hoped that the flavor of those pickles would reflect an inherent “me-ness” — that the microbes from my skin would mix with the microbes in the bed and infuse the resulting nukazuke pickles with a flavor that reflects my involvement, touch, and care.

And yet. I didn’t toast the rice bran. I didn’t use fine sea salt. I used tap water. I’ve already let them down. I thought about scrapping the bed I had started and making a new one. One that had perfectly toasted rice bran, purified water, the finest sea salt. But I’ve decided to give it a chance to survive and just see what happens — maybe the microbes will be fine despite not having been given the perfect start. Maybe I should start a new bed. Maybe I will.

--

I worry. I didn’t recognize that as a potentially not-great thing for myself until I started working with my current therapist. In our first session, I went in thinking I knew exactly what I needed to work on, telling him that I want to stand up for myself more and I’m bad at comforting my friends when they’re upset. I felt like I didn’t advocate for myself enough and like I wasn’t socially adept enough to know exactly what other people wanted or needed right when they needed it. He asked a couple follow-up questions, then — after I explained the various ways in which I felt broken and bad and wrong — paused, nodded, and responded, “I see. I hear that you want to make your friends feel valued

and loved and special. But I also think that you, yourself, need to feel valued and loved and special.”

In retrospect, of course! But at that time, I lived in deep Bushwick off the Chauncey J and felt like even asking people to come out there to hang out was too much of a burden unless I made it worth the trip. Usually through big, elaborate meals. My twenty-fifth birthday, for example. I bought five dozen oysters, several bottles of prosecco, fancy bread from a distant bakery, made compound butter with sea salt and fresh herbs, baked a flourless chocolate cake, and made whipped cream. And after all that effort — including traveling between Chelsea, Park Slope, Bushwick and Williamsburg before then learning how to shuck oysters online — I experienced most of the party from a distance, separated from everyone else by the kitchen counter. Rather than mingling and spending time with everyone who traveled out to see me, I shucked all 60 oysters while drinking too much wine and only talking to people in short snippets before blacking out and forgetting the last three or four hours of the evening. And that’s just how I handled most social interactions at the time: keeping people at a safe distance while catering to their needs and not taking my own experience into account. I just wanted to make everyone else happy. Which is fine when hosting a party, but I carried that mentality with me into every other facet of life. So, when my therapist told me that he sees and understands how badly I want to make other people happy but that I was doing it at my expense, I wept.

My first therapy homework assignment was to cook with — not for — someone else. It was meant as a metaphorical and practical exercise for letting go of control and trusting others to meet me in the middle. I had to learn that I don’t have to curate experiences for others to justify my presence and wants and needs. I can create and live in experiences alongside them. I try to see the tap water nukadoko bed through this lens. I’m not in control of the process. I’m not in control of the outcome. I’m learning as I go. We’re in it together.

--

The process of maintaining the nukadoko is a little bit of a black box. Now that (I think) my bed has fermented, it’s found a new home in my fridge so that I only have to mix it once a week rather than every other day. I periodically take it out from the fridge and, starting from the upper right corner of the container, dig my fingers into the cold, damp mixture until I find the bottom and gently dislodge the compacted nuka. Over the weeks, the bed has become much softer and more pliable as though the rice bran’s grit has been worn down. I move methodically, digging a winding path that snakes around the container, unearthing buried vegetables along the way. As I work my hands through the nukadoko, my mind goes elsewhere.

He remembered that, after digging for a little, the water oozes round your finger-tips; the hole then becomes a moat; a well; a spring; a secret channel to the sea. As he was choosing which of these things to make it, still working his fingers in the water, they curled round something hard—a full drop of solid matter—and gradually dislodged a large irregular lump, and brought it to the surface. When the sand coating was wiped off, a green tint appeared.

VIRGINIA WOOLF, 1918

I first read Solid Objects in high school. As a fifteen-year-old, I’m not sure how much meaning I pulled from the story at the time, but I’ve always loved this passage. The main character starts out ambitious and career-oriented until that day at the beach when he finds this first object in the sand. From then on, he abandons everything in service of collecting these concrete, tactile things that bring him joy and meaning, despite the criticism and misgivings of those around him. To me, people who maintain multiple ambitious fermentation projects seem to have tapped into a similar state of mind. They’re just better than everyone else. Other people whose fridges are full of old takeout containers and wilting vegetables instead of jars of homemade pickles and kombucha could never understand. Fermenters are in touch with nature. Their gut health must be impeccable. They have everything under control. Their social media presence underscores this. I’m jealous of their peace. Perhaps in an attempt to join their ranks, I’ve shared a few glimpses of my nukadoko process and maintenance online.

Does this story show that my life is going well and I’m doing such a great job of taking care of myself that I can also maintain a microbial community in my fridge that loves me and gives me pickles in return?

Can they tell I don’t really know if I’m doing it right?

I brush the sandy nuka off each wilted vegetable piece and set it aside so I can continue to mix the nukadoko, alternating between digging my hand into the bed and breaking up soft clumps between my fingers and thumb. The process is much more physical than I thought it would be. In the beginning I was clumsy and didn’t know how much pressure I needed to use when breaking up the compacted paste, so I frequently overestimated, flinging chunks of rice bran across my kitchen.

I’m better at it now. But still haven’t achieved the level of grace on display in videos of other people mixing their nukadokos. I wonder if their microbes are happy. It’s also more work than I expected it to be. I had a romantic notion in my head that I would find pleasure, joy and satisfaction in the process of taking care of it. I forgot that I’m a messy person who doesn’t find pleasure, joy or satisfaction in everyday household chores. And maintaining the nukadoko has become just another chore.

Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time (lit.) The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom

MIERLE LADERMAN UKELES

MANIFESTO FOR MAINTENANCE ART, 1969

Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote the Manifesto for Maintenance Art in 1969 at a point where she was struggling to come to terms with the intrinsic tension between being an artist and being a mother. The manifesto redefines the work required to maintain and care for her family, her home, and herself as acts of artmaking in the face of a world that devalues maintenance work and caregiving.

I’ve been struggling lately. I’m not finding joy in maintenance. Not in caring for the nukadoko, nor in taking care of myself, my cat or my environment. Outside of the refrigerator where my nuka waits patiently to be handled and fed, dishes are piling up. Mail is stacked on the counter. Laundry hides behind my bathroom door. The nukadoko and I both need to be refreshed, aerated, taken care of, but I don’t have the capacity for either of us these days. I don’t feel connected to my nukadoko or to nature or to myself. I wanted the nuka to help me access an imagined connection to nature that seems to ooze from more enlightened fermenters’ posts online. I’m struggling with my own little fermentation project because I’m struggling in other parts of my life right now. And I’m afraid that I’m harming the microbes as a result.

--

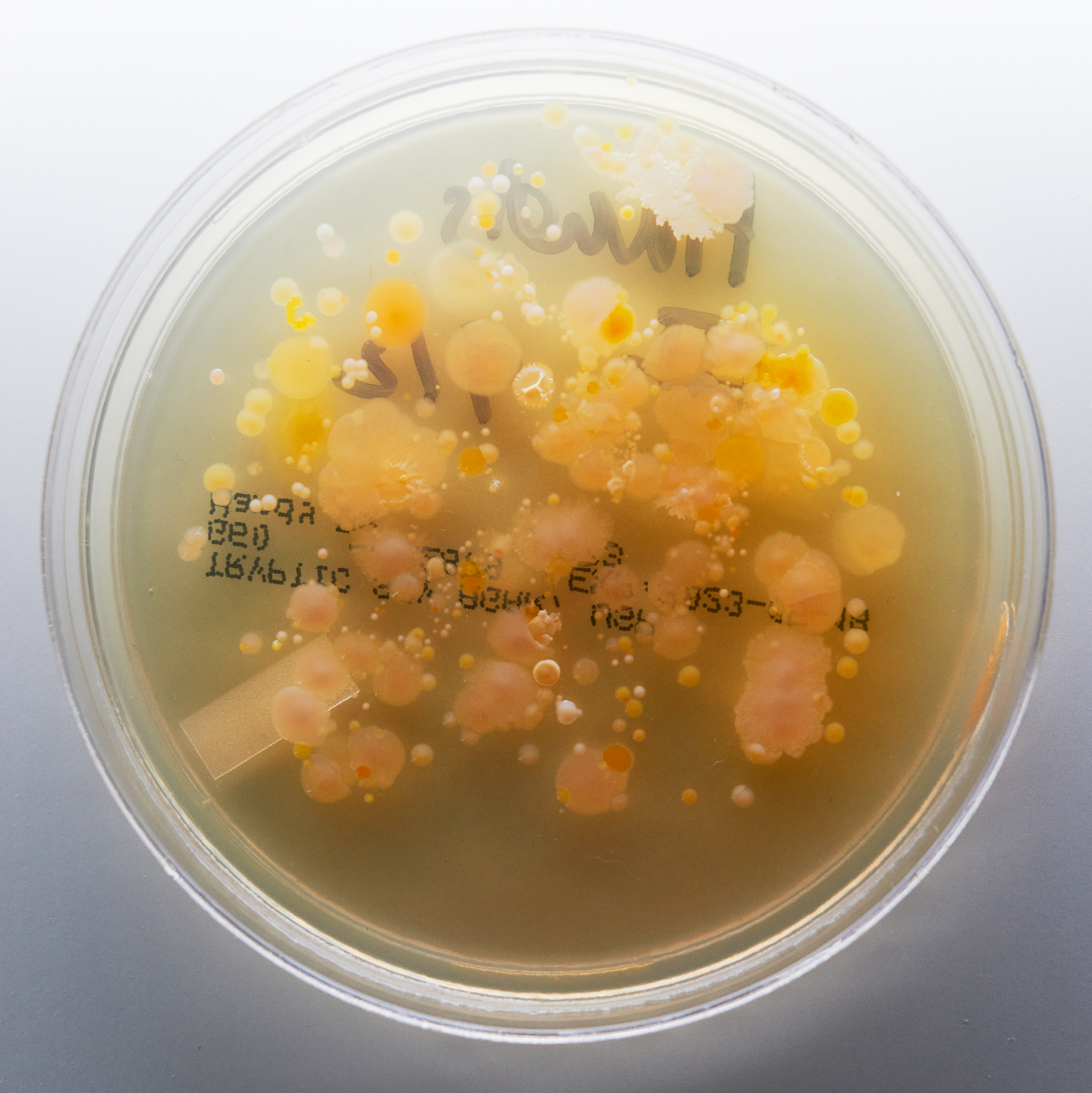

My nukadoko is now about 10 weeks old. I still have no idea if it’s happy and healthy. I want concrete proof that I haven’t failed. And I want to see if there are any similarities between the microbes on my hands and the microbes within the nukadoko — searching for evidence of my care. So, I decide to cultivate the microbes from the nukadoko in hopes of meeting them face to face. I order two types of agar plates — Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) and Lactobacilli MRS —from Amazon. They arrive wrapped in plastic and sweating slightly. The TSA plates are meant for the cultivation of microbes in general and don’t favor any particular kind. The Lactobacilli MRS medium, though, should deter the growth of any other kind of microbes besides Lactobacillus, which I’m told is what lives in the nukadoko bed.

To inoculate the plates, I started with the four hand plates and just touched the surface with my fingertips, tracing an invisible pattern across the cold jelly surface. Then for the nuka plates, I scribbled a piece of kombu from within the bed on the top of the medium for two of the plates. For the last two, I sprinkled a pinch of the nuka on top and pressed it down gently so that it wouldn’t become dislodged. The plates, much like the nukadoko itself, don’t give me any indication of whether I’ve done it successfully. I label the bottom of each one and tuck them into the spice cabinet, leaving them to grow.

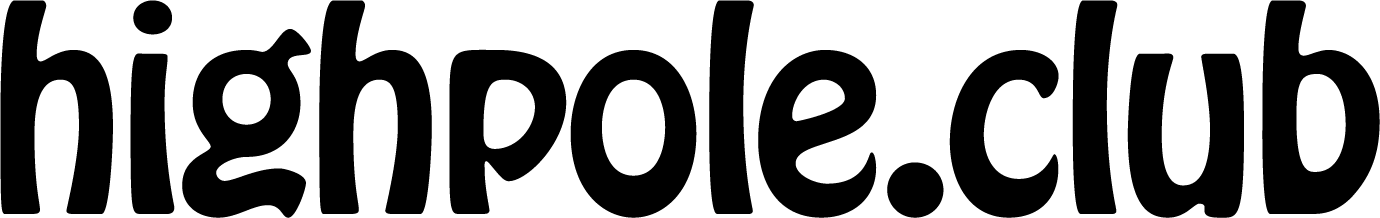

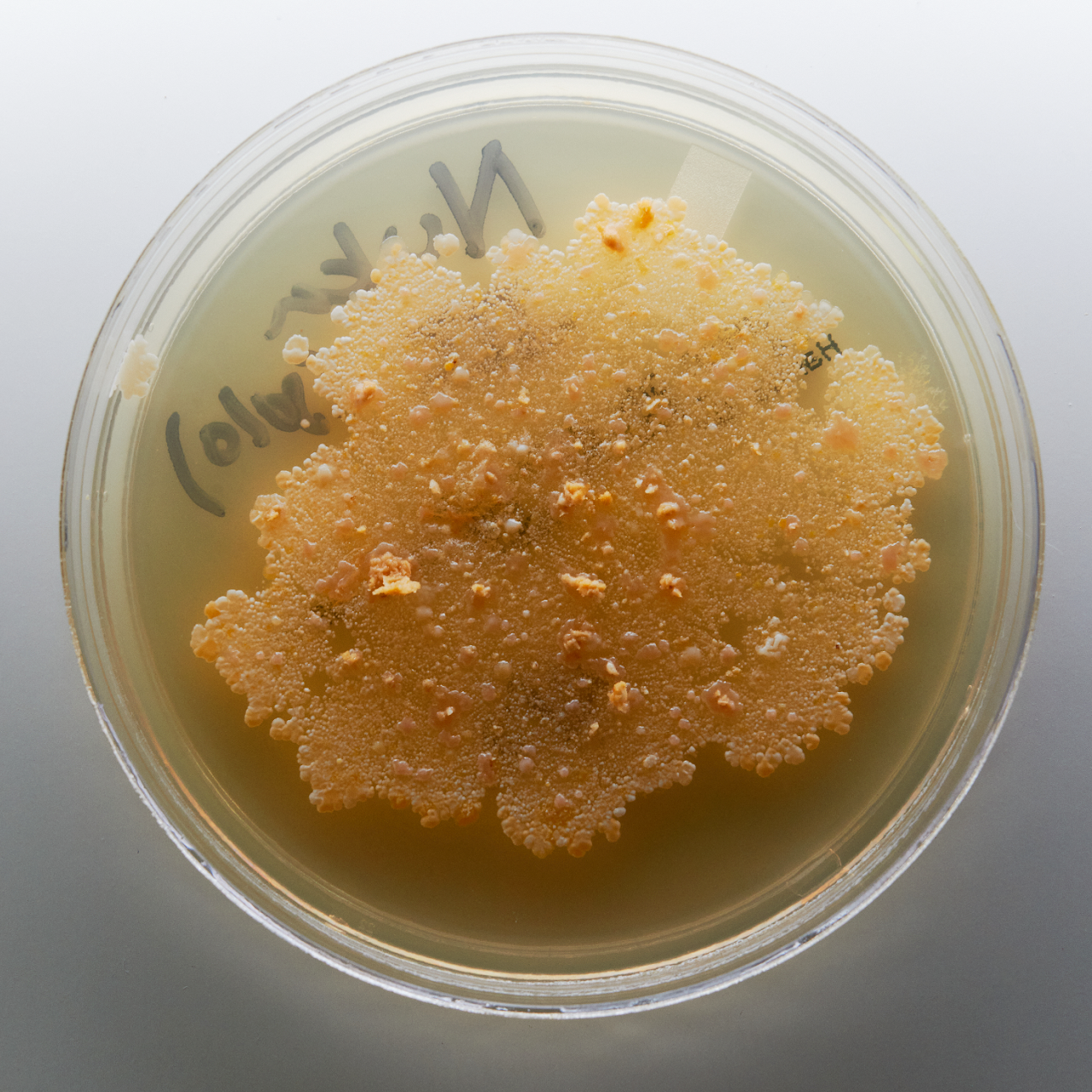

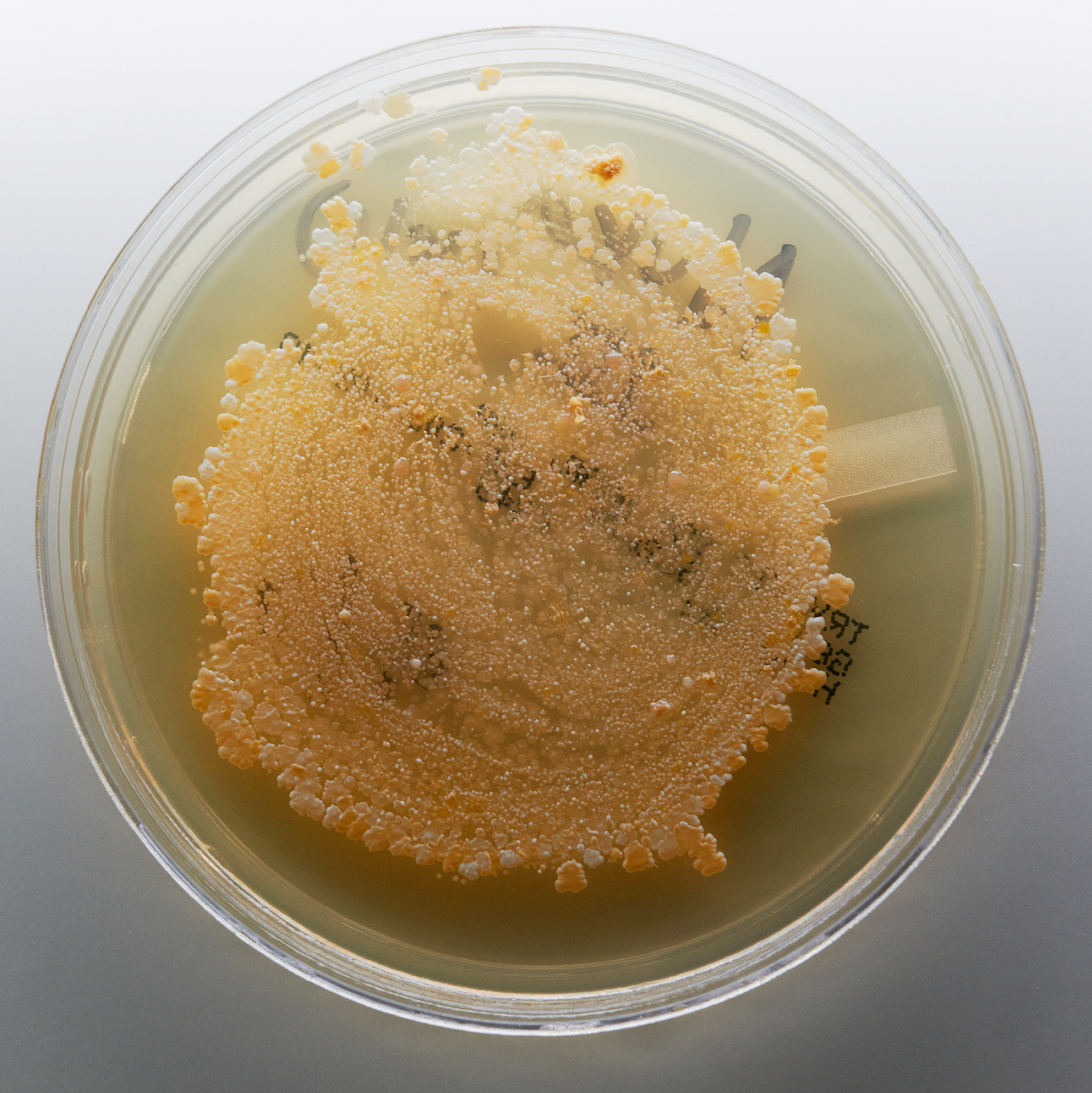

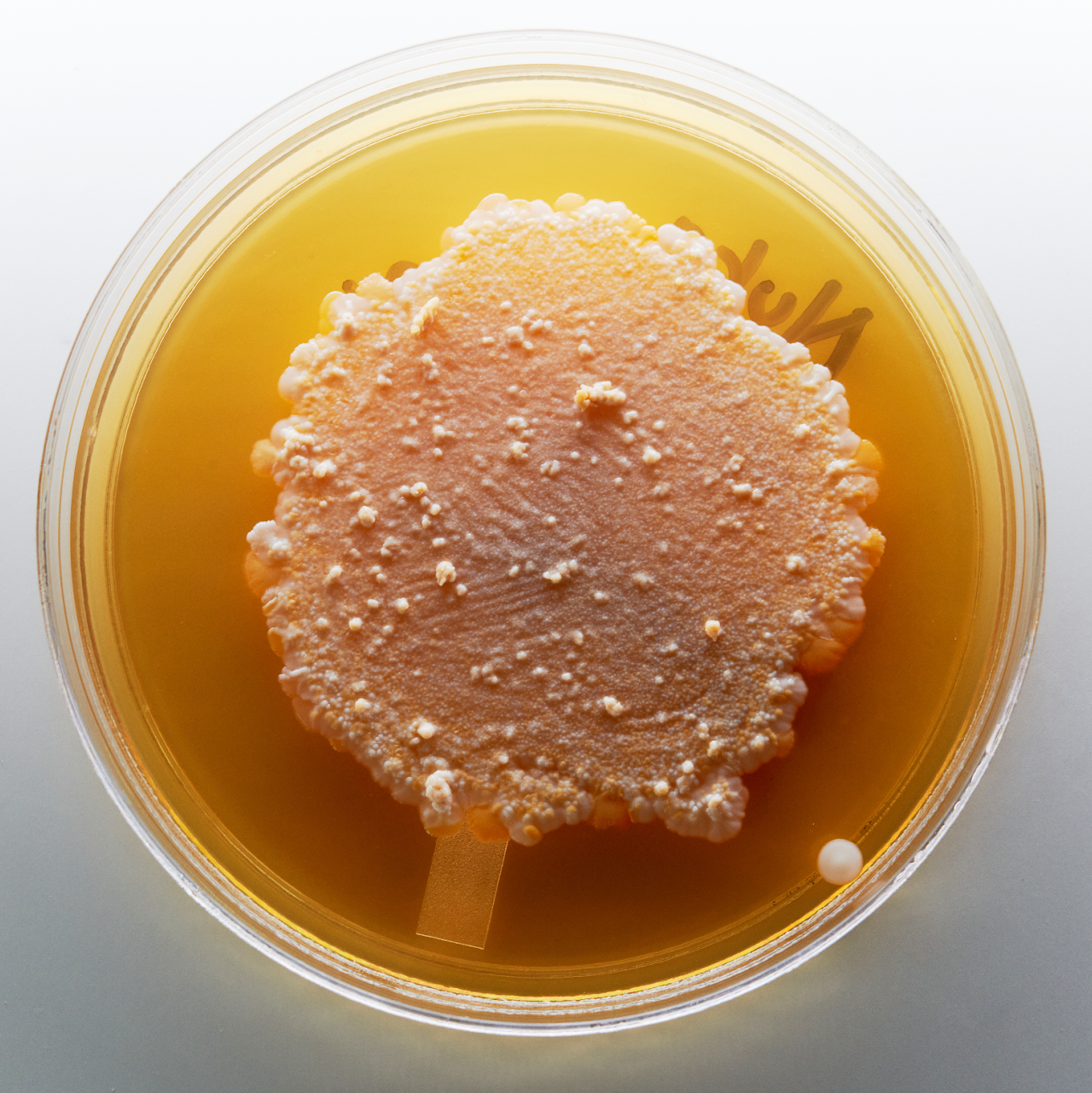

Four days later, all the nuka plates are coated in creamy, off-white bacterial colonies that look nearly identical to each other. The plates I cultivated my hands’ microbes on, however, look nothing like them. The Lactobacillus MRS agar hand plates have erupted in bulbous pinks and blossomed with teal, brown and white mold, while the TSA plates were demure with pale yellows, oranges and whites scattered across the surface in lacy patterns. On the one hand, I’m relieved to have cultivated Lactobacillus in the nukadoko. But I’m also disappointed to not see any similarities between the different microbial cultures. I’m not sure what I’m looking for anymore.

What is my role in the lives of the microbes? Am I their mother? Keeper? Friend? Caregiver? And what do each of these roles say about me? Does it even matter?

NUKADOKO PLATES

Cultivated TSA plates (top two) and Lactobacillus MRS agar plates (bottom two)

HAND PLATES

Cultivated TSA plates (top two) and Lactobacillus MRS agar plates (bottom two)

II. FINGER-, TONGUE-, TEETH-, NOSE-, AND EAREYES

I continue maintaining and feeding the nukadoko. I don’t know what else to do. Every week I rinse off the fermented vegetables and store them in an old soup container in the fridge next to the bed’s enamel home. The microbes are prolific. They produce far more pickles than I eat on a regular basis. But I’m proud of them regardless. I love feeding them raw green beans — texturally the beans are tender-crisp, as though they’ve been blanched and shocked. They’re salty at first, tinged with an underlying earthy funk passed down from the nukadoko, followed by the center that still tastes of raw green bean, reminding you that the vegetables also play a role in the process.

Because I have neither tapped into fermentation enlightenment nor found proof that the resident microbes have taken on any of my traits, I begin to just observe changes in the nukadoko paste as I maintain it. Learning how it reacts to different vegetables and feeling, tasting, smelling, and hearing changes in its form with my fingers, tongue, nose and ears. Now that we’ve been living together and interacting with each other for almost three months, the nuka has become softer and wetter, thanks to the radishes and cucumbers that have lent it their moisture. These days, scraping, scooping, and fluffing the nuka sounds and feels like I’m molding something out of playdoh: soft yet scratchy at the same time. Bits of the paste cling to my fingers and to the vegetables. I do my best to keep it all inside the container. The smell is hard to describe. Toasted and earthy but also sour. The smell makes the back of my jaw tingle, and my mouth waters reflexively. After spending two to four days planted in the bed, vegetables become infused with this scent and flavor. I replace them with fresh vegetables and press the nuka back into its bed. My palm clings to it a little, making a damp sound like two wet bodies coming together.

I mix the nukadoko less timidly these days, no longer worrying if I’m doing it right or if the microbes are there (they are)4. I’m learning to find pleasure in feeding the bed, delighting in the ways that the microbes respond to new foods. I try to see the maintenance work as collaboration. Borrowing my therapist’s metaphor, I’m trying to cook with the microbes now, not just for them. Through trial and error and paying more attention, I’m starting to learn the ways that the nukadoko communicates its needs through its texture, flavor, smell, and sound. And from that, I’m learning to see the ways in which I’m also communicating my own needs through my environment — evidenced by the piles of unopened mail, dirty dishes and recycling precariously stacked next to the garbage can.

--

Summer 2021 I moved into an apartment by myself for the first time as an adult in a space that I loved. It was sunny and cozy, and it was the first time I bought furniture and put shelves and art up on the walls of my home. A year later, when I was fully settled in the space and in my new neighborhood, the landlord raised the rent by 20% with twelve days left on my lease. My friend and I went for a walk around this time, catching up on life and airing out the grief in each of our lives. After wandering around for a couple hours, we stopped off at my doomed apartment where the kitchen table was obscured by dishes, unopened mail, recycling I hadn’t yet taken out. Embarrassed about them seeing how thoroughly I was failing to take care of myself, I started sorting the mail and scattered recyclables into piles. My friend assured me it was fine, and I should stop fussing, they didn’t mind the mess. When I didn’t stop, they handed me the pile of mail I had made moments prior and told me to go through it while they took care of the dishes. I wept with relief and appreciation and grief.

I’m trying to learn how to show up like that for the nukadoko and for myself — recognizing the current the chaos of my apartment as evidence of my needs and emotional state rather than as a sign that I’m failing myself.

Before I first started the nukadoko bed, I and all my colleagues were laid off. About three or four weeks into starting the nukadoko bed, I had a sparkly new job with a better title and a higher salary. And three weeks later, after working an 80-hour week and stress crying in multiple Zoom meetings, I put in my notice and left three weeks later. The day after my last day, I spent five and a half hours deep cleaning my apartment. As I cleaned, I imagined myself — the solid part that acts and makes decisions — as a symbiont to myself — the soft part that feels and reacts — collaborating to take care of my environment — the physical space that all parts of myself inhabit and express themselves through. I imagined myself as the microbes in the nuka that make do with the food, moisture, and oxygen available to them in their little container inside my fridge inside the kitchen of the new apartment I moved into soon after weeping with my friend in my previous apartment’s kitchen.

--

It’s been a few weeks since I’ve mixed and fed my nukadoko, the longest I’ve ever gone without taking care of them. I take off the container’s lid and find the entire surface coated in a familiar creamy off-white.

It’s nice to see them like this again.

Akiko & Peter; “Nukadoko (A Fermented Rice Bran Bed for Pickling),” Plant-Based Matters, 12 Aug 2021. https://plantbasedmatters.net/nukadoko-a-fermented-rice-bran-bed-for-pickling/

Hayward, Eva. 2010. “Fingereyes: Impressions of Cup Corals.” Cultural Anthropology 25 (4): 577–599.

Heldke, Lisa. 2018. “It’s Chomping All the Way Down: Toward an Ontology of the Human Individual.” Monist 101 (3): 247-60. https://doi.org/10.1093/monist/ony004.

Hey, Maya. 2021. “Attunement and Multispecies Communication in Fermentation.” Feminist Philosophy Quarterly 7 (3). Article 4. https://doaj-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/article/c084f8394f2143e2ac41afcebbda2a7e.

Ukeles, Mierle Laderman; “Manifesto for Maintenance Art,” QueensMuseum.org, 1969. https://queensmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ukeles-Manifesto-for-Maintenance-Art-1969.pdf

van Dooren, Thom; Kirksey, Eben; and Münster, Ursula. 2016. “Multispecies Studies: Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness.” Environmental Humanities 8 (1): 1–23. http://read.dukepress.edu/environmental-humanities/article-pdf/8/1/1/408987/1vanDooren.pdf.

Woolf, Virginia; “Solid Objects” in Woolf Short Stories, a Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook, 1920 (posted Oct 2002). http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200781.txt